The following is a re-publication of an article published in the CFNU’s Canada Beyond COVID magazine. To see the article in its original context, click here.

“Why are nurses stretched to the limit? It’s workload.”

Ivy Bourgeault is a professor at the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa. As part of her research, she regularly interviews nurses about their work. Stressors come from multiple sources, Bourgeault explained. Like all of us, nurses also have to contend with stress from their life outside work. But despite this, Bourgeault’s research has consistently revealed workload to be nurses’ number one issue.

The short-staffing of nurses is a longstanding problem. With nurse shortages endemic across the country, patients suffer longer wait times, deferred services and reduced care.

This has only been exacerbated by COVID-19.

“In the pandemic, we have people stressed, working really, really hard – working beyond their capacity,” explained Bourgeault. “They were doing that before; now, it’s in a crisis. And so they feel responsible because we’ve socialized health workers to [feel] responsible for this. And it’s all on their backs.”

“And those backs are breaking; they’re breaking mentally, they’re breaking physically.”

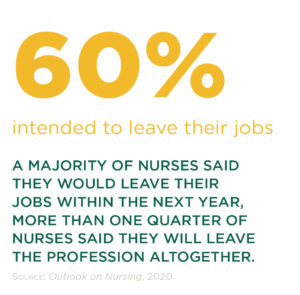

Without the proper support – and with the increased pressures brought on by the pandemic – nurses are quitting their jobs in droves, and some are leaving the profession altogether.

According to Statistics Canada, there were over 100,000 vacancies (end of 2020) in health care and social services. In Quebec, the number of nurses calling it quits, was up 43 per cent in 2020 compared to the previous year.

The pandemic has wrought an agonizing toll on the lives of nurses, but perhaps most acutely on their mental health. Mental health supports are crucial; they’re needed right now and into the future. But we got here largely because of inadequate staffing, and that’s a problem that needs to be tackled upstream.

Bourgeault admits that nurses might not be excited to hear that what’s needed is data, but the truth is that Canada has very little staffing data when it comes to nurses.

“We have lots of data for physicians,” she explained. “The data on nurses is separate. It’s not as robust.”

One of the reasons why the data is so much better for physicians, Bourgeault explained, is that they’re thought of as a cost driver in a publicly funded health care system. And because of fee-for-service, it’s much easier to keep track of what physicians are doing.

“We don’t have that for nurses; we aren’t able to say what nurses are doing because they’re not pay-for-service; they’re on salary in hospitals.”

While no one is arguing nurses should be fee-for-service, this does mean that the data we have on nurses is often insufficient to make key decisions in a public health care system. Proper health workforce planning depends on our ability to bridge the gap between the population health needs and our capacity to meet those needs.

“Are there sectors where we aren’t using nurses to their full potential, taking into consideration what nurses are trained to do and the needs of the population?” Bourgeault asked. It’s just one example of how Canada could develop a more adaptive health care system, if only it had the data to drive that kind of thoughtful decision-making.

But as things stand, governments in Canada are largely working in the dark. Instead of a systemic approach, Bourgeault said, governments are frequently making “one-shot policy interventions”, such as offering premiums to draw health care workers to a certain sector, without a model to predict the potential effects on other sectors.

This failure to plan is costly: the health workforce accounts for more than 10 per cent of all employed Canadians, and represents two thirds of all health care spending.

Proper health workforce planning exists in other countries. Bourgeault pointed to Australia and New Zealand, which have better workforce planning models and also fared better during the pandemic. Even the United States, she said, has better data on nurses, including race-based data.

“We don’t have any of that. From an equity lens, that’s unacceptable.”

The issue of equity is something Bourgeault is especially passionate about. She’s known for saying “gender always matters”. In the case of health workforce planning, gender matters too. Women make up 70 per cent of the global health care workforce; in Canada, it’s over 80 per cent, with women making up 90 per cent of the nurse workforce.

The kind of robust workforce data and planning Bourgeault would like to see applied to health care already exists in Canada: in the construction sector. BuildForce Canada collects data on construction workers to study and forecast long-term trends in that workforce.

It’s an industry-led organization that receives government funding to provide labour market information.

The organization has a number of modellers, Bourgeault explained. Their data feeds into a scenario-based forecasting system, which they use to assess future labour market conditions.

“There’s a robust infrastructure there,” said Bourgeault. “What’s the difference between the health workforce and the construction sector?”

“It’s not rocket science. Why it’s not happening for the health workforce sector in Canada is beyond me.”

—

Ivy Bourgeault, PhD, is a professor in the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa, and the University Research Chair in Gender, Diversity and the Professions. She leads the Canadian Health Workforce Network and the Empowering Women Leaders in Health initiative. Bourgeault has garnered an international reputation for her research on the health workforce, particularly from a gender lens. Recent projects focus on care relationships in home care and long-term care, and on the psychological health and safety of professional workers. Bourgeault was inducted into the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences in September 2016 and received the 2016/2017 University of Ottawa Award for Excellence in Research.

| To read more on this topic: Outlook on Nursing: A snapshot from Canadian nurses on work environments pre-COVID-19 assessed Canadian nurses’ perceptions of their work environments. The study highlighted how nurses’ work environments impact their health and work outcomes. Addressing the issues identified in this report is critical to ensuring a sustainable nursing workforce in the future. |

|---|