The following is a re-publication of an article published in the CFNU’s Canada Beyond COVID magazine. To see the article in its original context, click here.

“It was a real aha moment.”

It was during a lecture about the impacts of racialization on health that Nicole Welch, a director and chief nursing officer at Toronto Public Health, had her eyes opened to the pernicious and pervasive effects of systemic racism on health.

“[The lecture] talked about the impact and the weathering effect – that slow eating away at our health and our well-being,” explained Welch.

“Because of the experience of racism, we’re always in this fight-or-flight response – a heightened response.”

This is the lived experience of people in oppressed communities. It’s commonly referred to as ‘minority stress’: people who belong to equity-seeking communities experience greater levels of stress as they navigate a society where they are regularly subjected to discrimination and prejudice. This higher baseline of stress not only impacts mental health, it also contributes to poorer health outcomes and chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

“It was shocking to me,” recalled Welch. She reflected on her own heightened stress level – how each day she was sending her two Black boys to school and wondering if “today is the day.”

“Is today the day I’m going to get that call that they’re not being treated equally?”

Welch said that while she carries that additional stress every day, she hadn’t consciously recognized its toll because it sadly is part of the everyday Black experience.

During the pandemic, our collective level of stress rose. And for some racialized people, navigating public spaces became even more unnerving, as the number of hate crimes and overt acts of racism increased. According to the Chinese Canadian National Council’s Toronto chapter, which has been collecting reports of anti-Asian racism across Canada, there were 1,150 such instances in the pandemic’s first year. While three quarters were verbal attacks, numerous physical assaults were documented.

Minority stress is just one of the factors that contribute to health disparities among racialized communities. These disparities existed pre-pandemic, but the pandemic brought them into sharper focus. In Toronto, Black neighbourhoods were especially hard-hit by COVID-19.

“It’s not because you’re Black that COVID likes you better,” said Welch. Systemic racism, she explained, segregates and relegates racialized people to particular spaces.

“Certain spaces – certain jobs – are for you. They’re living in communities that are more densely populated. Because of lack of opportunity – because of racism – you can’t get the jobs you want.”

Welch pointed to research by Philip Oreopoulos, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Toronto. In 2009 and again in 2012, Oreopoulos sent thousands of randomly manipulated resumes to job recruiters in Canada’s largest cities. Both experiments revealed that “substantial differences in callback rates arise […] from simply changing an applicant’s name. Oreopoulos’ research found that candidates with English-sounding names were 35 per cent more likely to receive a callback than candidates with Indian or Chinese names. A similar study in the US found that applicants with white-sounding names were 50 per cent more likely to get callbacks than applicants with African American-sounding names.

It’s just one example of how implicit or unconscious bias works to disadvantage Black, Indigenous and people of colour. And while conversations about racism can often focus on overt acts, such as hate crimes and racial slurs, studies like these point to a more subtle form of racism that is just as harmful – that impedes upward social mobility and contributes to health disparities.

“We know that in any pandemic, whoever is at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder is going to be impacted,” emphasized Welch. “In our society in which we deal with racism, it is going to be Black, Indigenous and people of colour.”

A society with greater racial equality, Welch explained, would still see the effects of the pandemic on poor and working-class people, but those impacts wouldn’t disproportionately affect specific racialized groups.

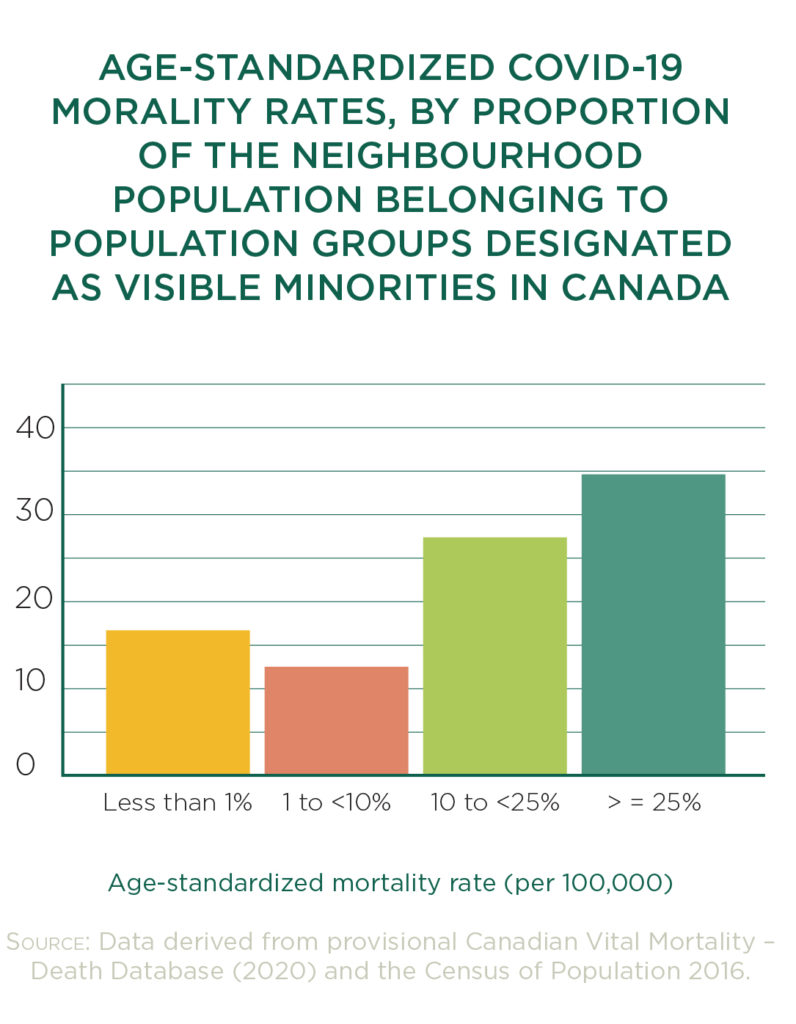

When Statistics Canada analyzed a year of COVID-19 data, it found that in areas where 25 per cent or more of the population was made up of “groups designated as visible minorities”, the mortality rate averaged 35 deaths per 100,000. In areas where racialized people made up less than one per cent of the population, the average death rate dropped to 16 deaths per 100,000. In Toronto, the data is even starker.

In November 2020, racialized people made up 79 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in the city.

Addressing COVID-19’s impacts on racialized communities requires immediate action. In the long term, Welch said, addressing the root cause of these impacts means decolonizing our institutions and tackling the systemic racism that permeates them. We simply can’t fix inequities without tackling the systems and structures that reinforce those inequities.

Since these populations have been especially hard-hit, getting vaccines into arms is critical. Public health officials have a tough job to do: they have to share evidence-based information with racialized communities in the hope of reducing vaccine hesitancy – and they have to do this knowing full well that they are working within a health care system that has all too often made these communities feel unwelcome, unheard and victimized.

Welch pointed to the tragic case of Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Atikamekw woman who endured racist taunts by health care staff as she lay dying in a Quebec hospital. And last year, British Columbia investigated allegations that ER staff played a game in which they tried to guess Indigenous patients’ blood alcohol level.

While the investigation failed to confirm the existence of this game, it did find widespread systemic racism. Indigenous patients reported being subjected to negative assumptions based on prejudice and racist attitudes.

Black patients’ health and well-being are also undermined by implicit bias in health care. As an example, Welch referred to studies in the US that looked at how Black patients’ pain is assessed and treated. According to a 2019 study that examined the treatment of acute pain in US emergency departments, Black patients were 40 per cent less likely to receive pain medications, compared to white patients, and 34 per cent less likely to be prescribed opioids. A 2016 study on racial bias in pain assessment and treatment found that half of first- and second-year medical students held false beliefs about biological differences between

white and Black people, including the notion that Black people’s skin is thicker than white skin.

Students who held these false beliefs rated Black patients’ pain lower and made less accurate treatment recommendations.

It also wasn’t long ago that Black and Indigenous bodies were used to carry out medical experiments. Between 1942 and 1952, First Nations children in six residential schools became the unwitting subjects of a nutrition study. Malnourished, these children were denied adequate food. The experiment continued, even as some children died.

From 1932 to 1972, the United States Public Health Service enrolled hundreds of Black men in a study that intentionally left their syphilis untreated to study the effects of the disease.

Participants in the study were lied to: they were told they were receiving proper medical treatment.

Today, the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the African American Male is often raised in the medical community as an example of racism so deeply ingrained that even the Hippocratic Oath was unable overcome it.

These historical harms have contributed to distrust of the medical community among Black, Indigenous and people of colour. Restoring trust will take time and concerted effort. As we work to dismantle systemic racism in health care, we must also create more welcoming spaces where people from all equity-seeking groups can feel seen, heard, validated and included.

Too often, it falls on the very people who are oppressed to call attention to issues of inequity and discrimination. The people who belong to equity seeking groups need allies – people in positions of privilege (yes, that means white people) – to step up to the plate. That means calling out racist and discriminatory practices, and examining our own assumptions, and how these ideas feed into implicit bias and uphold systemic racism.

“I’m a Black person.

I have my Master’s in nursing. Any time I go into a hospital to care for a family member – it’s sad – but I feel I have to say: ‘This is who I am. I’m a nurse. I’m well-educated. I know what’s going on here.’”

“I’m already assuming that the potential for my family member to not be treated fairly is there,” explained Welch.

“I shouldn’t have that added stress.”

—

Nicole Welch, RN, graduated from McGill University in 2000 with a Masters of Sciences in Nursing. She worked at Brampton Memorial Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. In 2001, Welch joined Toronto Public Health where she is currently the Chief Nursing Officer and COVID-19 Liaison Director. Welch is passionate about issues related to health equity and social justice, and supporting the development and maintenance of healthy communities. Welch’s passion for lifelong learning has led her to the final stages of a PhD in Applied Psychology and Human Development at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

| To read more on this topic: The CFNU’s Equity and Inclusion Toolkit provides resources to support our nurses’ union membership advocacy for a more just and equitable society. The toolkit contains a range of materials, including: FAQs, an introduction to using an equity lens, an inclusive language glossary, organizational and event accessibility checklists, sample workshops and sample policies. |

|---|