The following is a re-publication of an article published in the CFNU’s Canada Beyond COVID magazine. To see the article in its original context, click here.

Dr. Courtney Howard, an emergency physician and a globally recognized expert on the impacts of climate change on health, wants to shift the conversation around climate change. She says one of the key lessons climate change activists drew from the COVID-19 pandemic is that they need a different approach; we need to drop the doom-and-gloom message and adopt a more empowering one.

The messaging around COVID-19 was particularly successful, Howard said, because it brought together subject matter experts and politicians – and it told Canadians that they could be part of the solution. The message was clear: if you do these things – wear a mask, stay home, wash your hands – we can turn this around. We’re all in this together.

“We only have so much mental health energy to deal with bad news in a given day,” explained Howard. For that reason, climate scientists need to move away from the disaster message and focus instead on a new message: the “let’s do this cool thing” message, as Howard puts it.

The COVID-19 pandemic was dire enough to quickly galvanize and mobilize a global community. It’s the kind of action climate advocates wish they could see take place on the global stage when it comes to tackling man-made climate change.

Despite repeated warnings from the scientific community, addressing climate change has all too often gotten the kick-the-can-down-the-road treatment. It was an existential threat, but a distant one. And until recently, as Howard pointed out, our population had never lived through a global crisis.

“Now, everybody knows what a crisis feels like and is a lot more highly motivated to avoid the future crises that they’re now much more able to envision.”

From her home in Yellowknife, Howard has seen first-hand the climate crisis unfold. In 2014, when her youngest child was just one year old, the region was engulfed by wildfire smoke due to unusually warm and dry weather. After braving an especially cold winter, residents of Yellowknife were asked to spend almost two and a half months of the summer indoors because the outdoor air quality was so poor.

“I was just thinking: ‘Wow, what is this doing to all these kids’ lungs?’”

That question prompted Howard and her colleagues to look at how the 2014 wildfires had affected her local community. They found that emergency department visits for asthma had doubled over those summer months.

“When I do media interviews around wildfires, almost every single time, I get the question: ‘Dr. Howard, is this the new normal?’ And every single time I have to say: ‘No, it’s going to get worse.’”

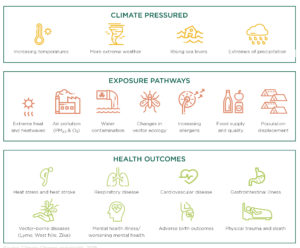

The World Health Organization considers air pollution a “major environmental risk to health”. According to the 2020 World Health Statistics report, the WHO states that air pollution “caused about 7 million deaths in 2016, largely as a result of stroke, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer and acute respiratory infections.” For its part, the Government of Canada estimates that air pollution contributes to 15,300 premature deaths per year.

And, of course, air pollution is but one health concern when it comes to climate change. With rising temperatures and increased flooding, climate change can lead to the proliferation of infectious agents such as such as dengue, malaria, hantavirus, salmonellosis, cholera and giardiasis. It also increases the likelihood of future pandemics.

“Most new infectious diseases have originated at the human-animal interface as a result of zoonotic spillover events,” explained Howard. “For that to happen, you need humans, animals and vectors in close proximity – and novel proximity.”

“That’s what climate change does: the habitat is changing, the temperature and precipitation patterns are changing, and we may be destroying habitat as well. That’s when these things happen.”

“Climate change puts us at risk of future pandemics exactly like this one.”

It’s an important connection to make – and one that the medical community is well-positioned to speak to. Nurses, Howard noted, are among the most trusted people in our society, regularly ranking in the top-3 most trusted professions. That’s why nurses’ voices are so desperately needed to make the connection between climate and health. Nurses have the power to move the conversation forward and galvanize support.

Howard said she used to spend a lot of time talking about the problem of climate change, but these days, she likes to tell the story of the coal power phase-out in Canada, which was accomplished largely as a result of advocacy by health care practitioners.

In Ontario, it started as a grassroots effort. In its report on Ontario’s coal phase-out, the International Institute for Sustainable Development highlighted how the Ontario Clean Air Alliance started with just six people and came to encompass “90 groups comprising over 6 million Ontarians in health care, unions, environmental groups, faith groups and municipalities.”

That movement inspired health care practitioners across Canada and helped secure a national and international commitment. The Canadian and British environment ministers founded the Powering Past Coal Alliance, which is now catalyzing work in this area across the globe.

“You can see how iterative progress inspires other people,” said Howard. “And we’ve done it. We know we can do it. And it was health messengers who led that.”

From a mental health perspective, there’s a rewarding feeling that comes from taking action, Howard explained. It not only helps us feel inspired, but it can help lessen our anxiety around climate change. And grassroots action is infectious: small wins build hope, and hope builds momentum.

When it comes to climate change, that people power is especially vital.

When the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives analyzed the lobbying efforts of the fossil fuel industry, it found 11,452 lobbying contacts with government over a seven-year period. According to the CCPA, the fossil fuel industry lobbied the federal government “at rates five times higher than environmental non-governmental organizations”.

“We’re getting completely outgunned from a communications and lobbying perspective,” remarked Howard. “And that, I believe, is the biggest obstacle. What our movement has, however, is people.”

Howard envisions the impact nurses could make to counter fossil fuel lobbyists. She’d like to see nurses, armed with PowerPoint presentations and briefing notes, making appointments with their MP to expose the linkages between health and climate change – to hammer home why we desperately need bold action to protect the health of Canadians by combating man-made climate change.

“I don’t think there would be a better way, in all of Canada, to move the ball on this issue,” she concluded.

“I’ve worked with nurses a long time; I do what nurses say.”

—

Dr. Courtney Howard is an Emergency Physician, a professor at the University of Calgary, and former president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE). For years, Dr. Howard has led climate change-related policy and advocacy work, including the 2017-2019 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Briefings for Canadian Policymakers, and acting as International Policy Director for the Lancet Countdown in 2018. Working with the World Health Organization Civil Society Working Group on Climate Change and Health, Dr. Howard’s advocacy, backed by a majority of the world’s health professionals, helped launch a Healthy Recovery initiative calling on G20 leaders to focus on low-carbon investments.

| To read more on this topic: Climate Change and Health sets out concrete steps and actions that nurses can take to act on climate change. Nurses know that patient health is closely tied to the patient’s environment. The paper lays out the major challenges ahead for health care and humanity as average temperatures continue to rise. It urges nurses to recognize the impacts of climate change on health and how we all must do more to reduce our impact on the planet, and prepare for the challenges ahead. |

|---|