The following is a re-publication of an article published in the CFNU’s Canada Beyond COVID magazine. To see the article in its original context, click here.

Throughout 2019, Nicholas Carleton, PhD, a psychologist and professor at the University of Regina, and Andrea Stelnicki, PhD, a post-doctoral student, were busy analyzing data they had collected from a survey of over 7,000 nurses across Canada.

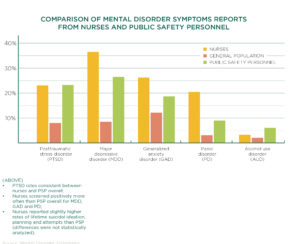

The results were shocking: nurses were grappling with an alarming number of symptoms indicative of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, burnout, panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Nurses were experiencing mental health disorder symptoms at rates consistent with police, paramedics and firefighters, all of whom experience mental health challenges at a higher rate than the general population.

At the time, nearly all nurses were reporting some difficulty with burnout, with nearly one third screening positive for clinical burnout.

Nurses were stressed, overworked, short-staffed and unsupported.

And then COVID-19 hit.

“If nurses had trouble with burnout before because of workload and stress, and then we add COVID, there’s every reason to believe that it’s more than a third that are having difficulty right now with clinically significant symptoms of burnout,” warned Carleton.

“I’m very worried about the pending fallout from COVID-19.”

The pandemic, Carleton emphasized, is a stressor like no other: it’s a global stressor. The stress brought on by COVID-19 wasn’t something nurses could simply leave at the hospital door; the pandemic has permeated every facet of our waking lives.

Nurses are tough as nails, but everyone’s resilience is finite.

In the end, Carleton explained, if your workplace is too stressful, if your workload is too heavy, if there’s not enough support from your employer, anyone can get worn down.

“It’s really just a matter of time. Because they’re humans.”Pre-pandemic, Carleton and Stelnicki’s research found that insufficient staff was the number one source of extreme stress: over 80 per cent of nurses said there weren’t enough staff to do their job, and almost three quarters said their institution was regularly over capacity. Excessive and mandatory overtime have become standard operating procedure, with nurses working themselves ragged, often at the expense of their mental health.

During the pandemic, the situation worsened. According to Statistics Canada, nurses’ average weekly overtime hours increased by 78 per cent in May 2020 when compared with the previous year.

COVID-19 won’t disappear overnight. With a vaccination campaign well under way, we are hopefully on the verge of seeing the virus recede, easing its heavy burden on our health care system. But as we eye a “return to normal”, we can’t accept a return to a broken system – one that barely had the capacity to handle a global pandemic.

“Right now, we need to start having more realistic conversations about expectation management,” explained Carleton. “We need to start doing staggered planning to make sure people have access to breaks – to make sure they have opportunities to access mental health care.”

Crucial in this will be to make sure that nurses know where to go to access evidence-based mental care, like cognitive behavioural therapy. But encouraging nurses to seek the care they need is no easy task; even nurses struggle to deal with the stigma surrounding mental health.

“There’s a tremendous amount of stigma,” explained Carleton. “Some of it is self-stigma – so, I’m being too hard on myself – and some of it is stigma from our colleagues, and some of it is [societal] stigma that we still have with respect to mental health.”

Key to preventing mental health disorders and injuries is knowing the early warning signs and where to get help. In his research, Carleton found that nurses are reluctant to reach out to mental health professionals for help, preferring instead to talk to friends and family. For this reason, family members and loved ones can play an important role in safeguarding nurses’ mental health; they will often be the first people to notice changes in mood and behaviour.

Nurses also need good preventive care. It’s important to take a mental health break: go outside, exercise, meditate, adopt a healthy sleep routine, keep a journal, open up to someone you trust – whatever works for you. These small daily habits can help safeguard our mental health.

In an ideal world, Carleton envisions people caring for their mental health much in the same way we care for our teeth.

“If I’m brushing my teeth every day, and flossing every day, that’s good,” said Carleton. “It doesn’t mean I’ll never have a cavity, but I do those daily little things that help protect my dental health. And at least once a year, I go for a dental check-up. It’s a systematic thing. We do it with intention.”

“So, how do we start shifting the population’s discussion so that we focus on mental health with as much care as we focus on dental health? I think that’s part of our next steps.”

—

R. Nicholas Carleton, PhD, is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Regina. He is a registered clinical psychologist in Saskatchewan, and Scientific Director for the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment. Carleton has published over 170 peer-reviewed articles exploring the fundamental bases of anxiety and related disorders. He has delivered more than 360 presentations at national and international conferences. Carleton has received several prestigious awards, is an inducted Member of the Royal Society of Canada’s College, a fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, and received the 2020 Royal Mach Gaensslen Prize for Mental Health Research.

| To read more on this topic: In 2019, Mental Disorder Symptoms Among Nurses in Canada surveyed over 7,000 nurses about their mental health in the first nation-wide assessment of post-traumatic stress injuries (PTSI), such as PTSD, generalized anxiety disorder, or major depressive disorder. To put the data into perspective, the report compared nurse data with the results for public safety personnel and the general population. |

|---|